Why Should You Perform Signal Detection in Early Phase Clinical Drug Trials?

The term ‘pharmacovigilance’ has conventionally been related with post-marketing activities; however, it is also equally applicable to the pre-marketing process for collecting, managing & assessing safety information during clinical development of the molecule. Similarly, the concepts of signal detection and assessment, risk assessment and risk minimization are as applicable to the pre-marketing scenario as they are to the post-marketing scenario.

The importance of this is evident from the following examples:

-

Drugs not approved in USA

– Examples of drugs not approved in USA as premarketing experience provided evidence of the potential for severe DILI e.g., Dilevalol, Tasosartan, Ximelagatran.

-

Drugs withdrawn from market worldwide after initial regulatory approval

– E.g., Rimonabant, Rofecoxib, celecoxib etc.

The safety information generated at the end of clinical development program should be extensive enough to permit comprehensive regulatory review and determination of benefit-risk profile for supporting marketing approval. The information should be comprehensive so that product label can be adequate to provide prescribers & patients adequate information for safe use of the drug.

What Do the Regulators Say?

USFDA 21CFR312.32 USFDA Draft Guidance on Sponsor Responsibilities

June 2021

Sponsors must adopt a systematic approach to safety surveillance to meet IND safety reporting requirements and enhance quality of safety reporting.

Such an approach involves promptly reviewing, evaluating, and managing safety information from all sources, including animal studies, clinical investigations, scientific literature, professional meetings, foreign regulatory authorities, and commercial marketing experience.

USFDA 21CFR312.56 USFDA Draft Guidance on Sponsor Responsibilities June 2021

– The sponsor’s review should involve assessing data from all sources and monitoring the progress of investigations:

- To identify previously undetected potential serious risks (§312.56(a)).

- To update investigator’s brochure, protocol, and consent forms with new information.

- As necessary, to take measures for protecting subjects (e.g. monitoring, modifying dosing, or participant selection) (§312.56(d)).

CIOMS Working Group VI

– The purpose of ongoing safety evaluation during drug development is to ensure that important safety signals are detected early and to have a better understanding of benefit-risk profile of study drug.

Sponsors should develop a system to analyse, evaluate and take actions on the safety information on a continuous basis. This is to ensure the earliest possible detection of safety concerns and allow suitable risk minimization.

Systemic Approach for Signal Detection

Essential Elements for Effective Signal Detection in a Clinical Development Program

- Early Initiation is Crucial

- Written Process Required for Review

- Multidisciplinary Safety Management Team (SMT)

- Data from Licensing Partners to be Considered

- Project Management Function

- Background Incidence

- Ready Data Accessibility

- Initiative Proactive Strategy

- Establish Timeframes and Milestones

- Decision Making

- Advisory Bodies

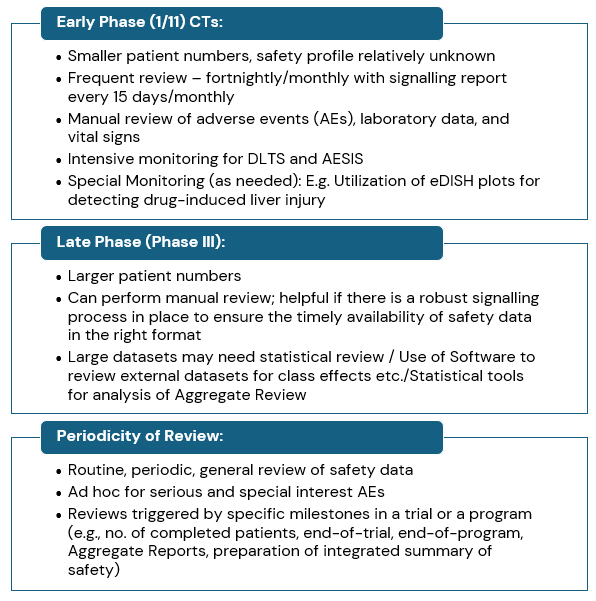

Signal Detection: Effective Data Review

Below are some of the key points that support effective data review during signal detection process in a clinical development program:

| Parameters | Overview |

| Analyse all AEs – Serious and Non-serious | The safety analysis is complete when all adverse events (serious and non-serious) are reviewed, with a greater emphasis on those leading to treatment discontinuation |

| Review of Individual Cases | Individual case analysis is essential for safety analysis. SARs and AESIs are important for detecting safety signals. Consider patient population, drug indication, and disease history during analysis. |

| Aggregate Review of Safety Data | Aggregate review helps analyse evolving safety information, comparing interval and cumulative data. Data should be analysed per dose, cohort, gender, age, etc. |

| Review of Clinical Lab Data | Laboratory tests are useful for screening subjects, early detection of organ toxicity & detection of potential toxic effects. Special focus should be on lab values correlating with organ toxicity e.g., endocrine abnormalities, hepatotoxicity etc. |

| Adverse Events of Special Interest (AESI) | The protocol should define AESIs, emphasizing identification, monitoring, and reporting. Includes events like rhabdomyolysis or hair loss. |

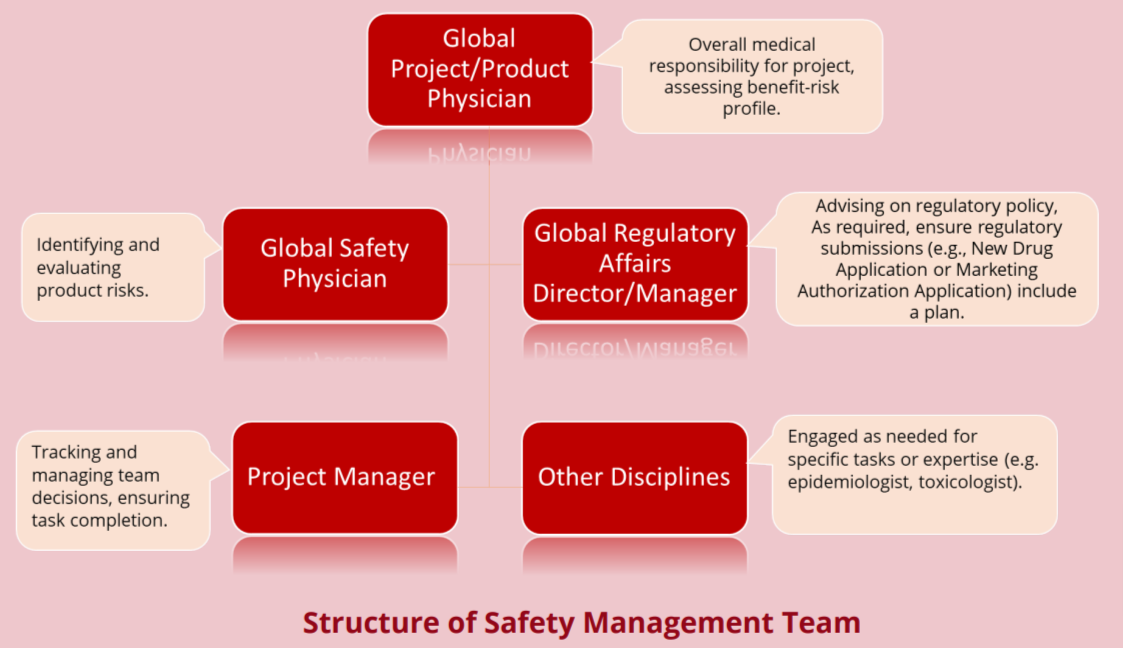

Structure of Safety Management Team

Development Risk Management Plan (DRMP)

A Development Risk Management Plan (DRMP) is a natural extension of high-quality pharmacovigilance. In DRMP, a compound-specific approach should be adopted, possibly as part of the broader Clinical Development Plan. It should contain early documentation of identified, expected, or potential risks, along with strategies for addressing them throughout development. As appropriate, the DRMP may develop into a post-marketing risk management plan.

The DRMP is a guide for safety surveillance during development and is not a legal or regulatory document; however, the following two actions must be considered during development of the process:

Recognize the potential for legal discovery of DRMP and ensure appropriate

language clarifying its status as a working document.

- Recognize the potential for legal discovery of DRMP and ensure appropriate language clarifying its status as a working document.

- Establish robust processes, including project management to ensure the diligent execution of the action plans.

The DRMP should include the following sections: anticipated product profile, epidemiology, non-clinical safety experience, clinical safety experience, identification and assessment of known or anticipated risks, identification and assessment of potential new risk, and actions and/or plans for evaluating and mitigating risk.

Conclusion

The concepts of signal assessment, risk assessment and risk minimization are as

applicable to pre-marketing scenario as they are to the post-marketing scenario. The purpose of ongoing safety evaluation is to ensure that safety signals are detected early and to obtain an understanding of benefit-risk profile of the drug. Signal detection during clinical trials is usually performed based on clinical judgement, since there is limited data available during premarketing clinical trials. The three basic attributes for signal detection includes quick medical assessment, periodic aggregate assessment, and safety evaluation of completed unblinded trials. To ensure effective signal management, it is important to establish an effective system, beginning early, having proactive approach, analysing all serious and non-serious events, periodic reviews by scientific committees, and prompt decision making.